News

Team day at The Don McCullin exhibition

Written by Arron O'Hare on Wednesday, May 29, 2019

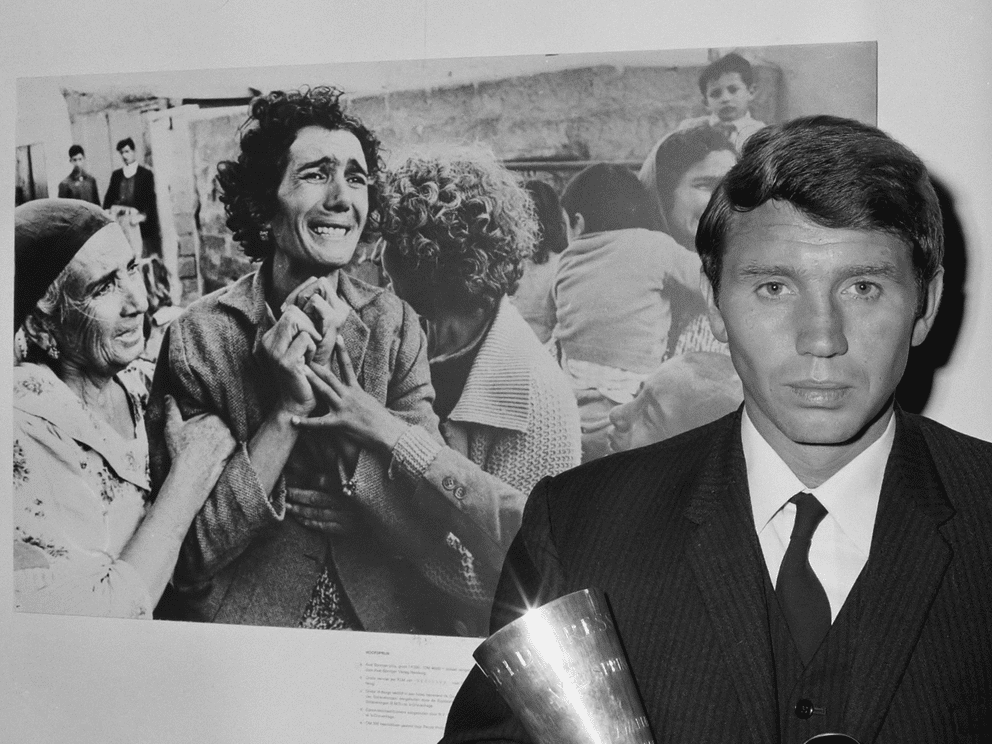

“Seeing, looking at what others cannot bear to see is what my life is all about.”

The Don McCullin exhibition, Tate Britain

Busy schedules permitting, we like to have agency ‘away days’ when we all take some time out, have a bit of team-building fun and take in a bit of culture.

This year the London advertising team descended en masse to the Don McCullin photographic exhibition hosted at Tate Britain and, for a little light relief and added danger, we then went axe throwing. (That’s another story but for the record it’s lots of fun and harder that you may think).

You may not have heard of Don McCullin but chances are you will be familiar with his work. He is perhaps most famous for the haunting image of a dazed, shell-shocked US marine, staring out into nowhere from beneath a grimy helmet with intense, unseeing eyes. It was one of many photographs McCullin took during his coverage of the Vietnam War.

Born in London in 1935, McCullin developed a keen eye for photography, capturing stark images of local gangs posing around the crumbling buildings and bombsites of 50s London. His talent caught the eye of newspaper editors and he was soon commissioned to work for The Sunday Times and The Observer. His assignments took him around the globe and across decades, documenting conflict, famine and the world at its very worst.

His images are astonishingly powerful, touching, raw and visceral. He claims not to be an artist but there is a definite art to his compositions, the way he has captured his subjects, and how he presents them to the world.

One of my favourite pieces of his work is part of a photo-story entitled, ‘War on the homefront’. It shows a street corner in Londonderry during the troubles. On one side of the corner is an armed patrol, bristling with weapons and riot shields. Creeping along the other side of the corner towards them is a teenager dressed in a suit and tie. His weapon of choice is a large plank of wood raised above his head.

His situation appears in turns futile, perilous, brave and almost darkly comedic. It’s David and Goliath in real life – one young man taking on an army with a just a stick.

It reminded me a little of some of Banky’s work in terms of the subversive nature of the image.

There was some light relief in his work, including a shot of a man and woman laughing as they competed in a knobbly knees competition at a holiday park, and some beautiful, ethereal images of elephants at a festival in India, but for me these moments of respite were swallowed up by the sheer volume of horror and despair in the frames that surrounded them.

A lifetime of documenting such events took its toll on McCullin. He is quoted as saying that he grew tired of the guilt of being able to walk away from the subjects in his pictures whilst they still suffered.

He retreated to his home in Somerset and now takes breath-taking photographs of the rugged, windswept landscapes that surround him. In his words, he is now ‘sentencing himself to peace’.

These landscapes are the last things you see in the exhibition because the curators understand the need, as did McCullin, to escape the ugliness and take in some of the beauty that also surrounds us.